In the grand theater of life on Earth, insects have played a starring role for over 350 million years. These tiny creatures, often overlooked or even despised by humans, are in fact the most successful group of animals the planet has ever seen. From the deepest jungles to the highest mountains, from scorching deserts to frozen tundras, insects have conquered nearly every terrestrial habitat. Their diversity is staggering - scientists have described over a million species, with estimates suggesting millions more await discovery. This raises a fascinating question: if evolution constantly drives change, why have insects remained so fundamentally similar in their basic body plan for hundreds of millions of years?

The secret to insects' enduring success lies in a perfect storm of evolutionary advantages. Their exoskeletons provide both protection and structural support while remaining lightweight enough for flight. The segmented body plan allows for incredible specialization of different body regions. Most importantly, their small size enables them to exploit ecological niches unavailable to larger creatures. A single tree can support dozens of insect species, each feeding on different parts of the plant at various life stages. This micro-partitioning of resources prevents direct competition and allows for remarkable biodiversity.

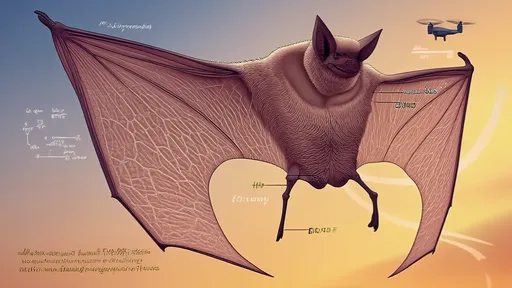

Flight changed everything for insects. The evolution of wings (a trait appearing in insects long before any other animal group took to the skies) granted them unprecedented mobility. Suddenly, food sources meters away became accessible, predators could be escaped, and new territories could be colonized. The energy efficiency of insect flight remains unmatched by any human aircraft - a honeybee can fly kilometers on the energy contained in a few drops of nectar. This aerial advantage created evolutionary pressure to maintain the basic insect body plan, as radical changes might compromise flight efficiency.

Reproductive strategies provide another key to understanding insect dominance. Most species produce enormous numbers of offspring, allowing for rapid adaptation through natural selection. A single female aphid can theoretically produce billions of descendants in one season. This explosive reproductive potential means genetic mutations (the raw material of evolution) appear frequently, while short generations allow beneficial traits to spread quickly through populations. Yet despite this constant genetic experimentation, the core insect architecture persists because it simply works too well to require fundamental change.

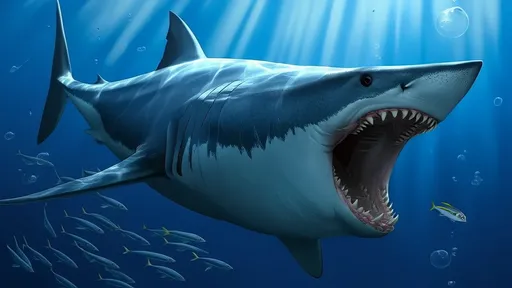

The concept of evolutionary stasis explains much of the insect paradox. When an organism's form becomes perfectly adapted to its environment and way of life, natural selection actually works to maintain that form rather than change it. Horseshoe crabs, crocodiles, and sharks demonstrate similar stability over geological time. For insects, the basic body plan reached such an optimal configuration that most evolutionary changes since have been relatively minor tweaks - different wing venation patterns, modified mouthparts, or altered antennae shapes - rather than wholesale redesigns.

Insects also benefit from what biologists call modular evolution. Their body segments and appendages can evolve independently, allowing for specialization without compromising the entire system. A beetle's hardened forewings (elytra) evolved to protect the delicate flight wings beneath, while leaving the flying apparatus itself unchanged. This modularity means insects can adapt to new ecological opportunities without having to reinvent their entire anatomy with each environmental challenge.

Human observers often make the mistake of equating physical change with evolutionary progress. But evolution has no direction or end goal - it simply favors whatever works. The cockroach's basic form has remained largely unchanged for hundreds of millions of years because it represents an ideal solution to a set of environmental challenges that have themselves remained constant. Modern cockroaches could likely interbreed with their Jurassic ancestors if time travel were possible, yet they've survived mass extinctions that wiped out seemingly more "advanced" creatures like dinosaurs.

Climate fluctuations throughout Earth's history have actually played into insects' hands. During warm periods, their numbers and diversity explode. When temperatures drop, their small size allows them to survive in microhabitats that remain tolerable. The Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that ended the dinosaurs' reign simply cleared the stage for insects to diversify further. Mammals eventually grew larger and more complex, but insects continued dominating in terms of biomass, species count, and ecological importance.

Modern human activity presents perhaps the greatest challenge insects have ever faced. Habitat destruction, pesticides, light pollution, and climate change are causing alarming declines in many insect populations. Yet even here, we see evidence of their remarkable adaptability. Urban environments have given rise to new populations of mosquitoes that breed in underground water supplies, and bedbugs that resist our strongest pesticides. The real question may not be why insects haven't evolved more, but whether humans will prove as evolutionarily resilient as these tiny titans of adaptation.

As we face an uncertain ecological future, perhaps we should look to insects not with disgust, but with respect. Their evolutionary stability represents not stagnation, but perfection - the kind that only hundreds of millions of years of refinement can achieve. The next time you swat a fly, remember: you're facing off against a life form whose ancestors saw the rise and fall of dinosaurs, witnessed continents drift apart, and survived global catastrophes that reshaped the planet. That's no ordinary bug - that's one of evolution's greatest success stories.

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025