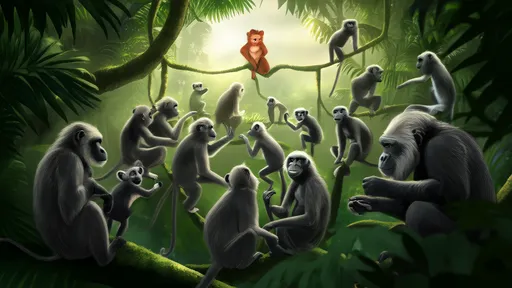

Deep in the Indian Ocean, off the southeastern coast of Africa, lies an evolutionary marvel—Madagascar. This island, the fourth largest in the world, has been isolated for nearly 88 million years, creating a living laboratory of biodiversity unlike anywhere else on Earth. Among its most iconic inhabitants are the lemurs, primates that have evolved into a dazzling array of forms, filling ecological niches that elsewhere are occupied by monkeys, squirrels, and even woodpeckers. These creatures are not just biological curiosities; they are a testament to the power of geographic isolation in shaping life.

The story of Madagascar’s lemurs begins with a dramatic geological event—the island’s separation from the supercontinent Gondwana. As the landmass drifted away, it carried with it an ancestral population of primates that would eventually give rise to all modern lemurs. Cut off from the evolutionary pressures of mainland Africa, these early arrivals diversified in ways that defy expectations. Today, over 100 species of lemurs exist, ranging from the tiny mouse lemur, small enough to fit in a human hand, to the imposing indri, whose haunting calls echo through the rainforest.

Isolation as an Evolutionary Catalyst

Madagascar’s isolation has acted as both a shield and a crucible for its lemur populations. Without competition from monkeys or large predators, lemurs radiated into an astonishing variety of forms. Some, like the sifakas, became expert leapers, their powerful legs propelling them between trees with balletic grace. Others, like the aye-aye, evolved bizarre adaptations—elongated middle fingers for extracting insects from bark, making them the world’s only primate version of a woodpecker. This evolutionary freedom allowed lemurs to exploit resources in ways that would be impossible on continents crowded with competitors.

Yet this isolation also carries fragility. Lemurs, having evolved without threats like large carnivores or aggressive primates, are ill-equipped to handle sudden changes. Many species exhibit "island syndrome"—traits like slower reproduction rates and reduced aggression, which served them well in stable environments but now leave them vulnerable. When humans arrived on Madagascar just 2,000 years ago, bringing deforestation, hunting, and invasive species, the lemurs faced pressures unlike any in their long history. The result has been catastrophic: since human settlement, at least 17 lemur species have vanished, their fossils silent witnesses to a lost world.

The Dance of Coevolution

Lemurs did not evolve in a vacuum. Their story is intertwined with Madagascar’s unique flora, particularly its towering baobabs and fruit-bearing trees. Many lemur species, like the critically endangered black-and-white ruffed lemur, are essential seed dispersers. Their digestive systems gently scarify tough seeds, which then sprout far from parent trees. Without lemurs, entire forest ecosystems would collapse. Similarly, the island’s giant leaping rats and tenrecs—small, spiny mammals—fill roles typically occupied by rodents or hedgehogs elsewhere, creating a web of relationships found nowhere else.

This coevolutionary tango is most striking in the case of the traveler’s palm and the lemurs that pollinate it. Unlike continental palms, which rely on wind or insects, this plant has evolved to depend solely on lemurs. Its flowers open at night, releasing a musky fragrance that attracts nocturnal species like the fat-tailed dwarf lemur. As the animals clamber through the blossoms, their fur collects pollen, which they carry to the next tree. Such intricate partnerships, forged over millennia, underscore how isolation fosters interdependence.

Modern Threats and Conservation Paradoxes

Today, Madagascar’s lemurs face a gauntlet of anthropogenic threats. Slash-and-burn agriculture, known locally as tavy, has reduced forests to 10% of their original cover. Mining operations for gems and nickel carve wounds into habitats. Even well-intentioned conservation efforts sometimes backfire; rigid protected areas can alienate local communities whose ancestors have lived alongside lemurs for generations. The irony is stark: the very isolation that allowed lemurs to flourish now makes their survival precarious, as fragmented populations struggle to adapt.

Yet there are glimmers of hope. Community-led reforestation projects, like those near Maromizaha Forest, combine lemur protection with sustainable vanilla farming. Researchers are discovering new species—such as the ghostly white Ankarana sportive lemur—using genetic tools, proving that Madagascar still holds secrets. Ecotourism, when managed ethically, provides economic incentives to preserve habitats. Perhaps most crucially, Malagasy scientists are taking leading roles in conservation, blending traditional knowledge with cutting-edge biology.

The tale of Madagascar’s lemurs is more than a chronicle of unique animals; it is a parable about the fragility and resilience of life. These creatures, shaped by an island adrift in time, now hang in a balance shaped by human hands. Their survival will depend not just on science, but on our ability to value evolutionary oddities not as curios, but as irreplaceable threads in the tapestry of biodiversity. As the indri’s song fades across shrinking forests, it carries with it a question: in an age of connection, can we learn to cherish isolation’s gifts?

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025